How have you been enjoying our latest imaginative foray into the wonderful world of formatting book manuscripts? If you’re at a loss for words to describe the experience, how about gee, this is complicated, but it’s thrilling to know at last that I’m doing it right? Or I’d been doing it right, I see, but how fascinating to know the logic behind it?

Heck, I’d even settle for well, it’s kind of a slog, but at least now I know that my entry won’t be disqualified from the First Periodic Author! Author! Awards for Expressive Excellence when I enter on or before May 18, 2009. Phew!

Okay, so standard may not be the most scintillating subject in the world, but since it actually is sometimes the difference between a well-written manuscript that strikes Millicent, everybody’s favorite agency screener, as well-written enough to keep reading beyond the first page or two and one that makes her exclaim, “Oh, too bad — this writer isn’t ready yet. Next!” I do feel better if we run over the basics two or three times per year.

As those of you who have been reading this blog for a while have undoubtedly noticed. Hey, at least you were already prepared to enter the contest; nothing at which you should be sneezing.

Another non-sneeze-worthy achievement: after you’ve been through the rules a couple of times, the difference between a professionally formatted manuscript and one whose writer just thought it looked nice that way should be almost instantaneously apparent. As, indeed, it is to anyone who reads manuscripts for a living.

Like, say, Millicent. Pity her; she has the unenviable task of trying to see past all of those weird formatting (and spelling, and grammar) choices in order to try to discover fabulous new talent.

Wipe that smirk off your face. Even if you aren’t in the habit of empathizing with people who reject writers for a living, there’s a good self-interested reason you should care about her state of mind: even with the best will in the world, grumpy, over-burdened, and/or rushed readers tend to be harder to please than cheerful, well-treated, well-rested ones.

Millicent is the Tiny Tim of the literary world, you know; at least the Bob Cratchits a little higher up on the office totem pole uniformly get paid, but our Millie sometimes doesn’t, or gets a paycheck that’s more an honorarium than a living wage. A phenomenon that one might expect to become increasingly common, by the way: the worse a bad economy gets, the better an unpaid intern is going to look to a cash-conscious agency.

Or, heaven help us, a worried publishing house that’s been laying off editors.

Even if Millie’s not an intern, she’s still unlikely to be paid very much, at least relative to the costs of living in the cities where the major publishers dwell. Her hours are typically long, and quite a lot of what she reads in the course of her day is, let’s face it, God-awful.

Not to mention poorly formatted. But that should be obvious to you by now, right?

Millicent’s job, in short, is not the glamorous, power-wielding potentate position that those who have not yet passed the Rubicon of signing with an agency often assume it to be. Nor, ideally, will she be occupying the position of first screener long: rejecting queries and manuscripts by the score on-the-job training for a fledgling agent, in much the same way as an editorial assistant’s screening manuscripts at a publishing houses is the stepping-stone to becoming an editor.

You didn’t think determining a manuscript’s literary merits after just a few lines of text was a skill that came naturally to those who lead their lives right and got As in English, did you? Agents and editors have to learn to spot professional writing in the wild — which means, in part (out comes the broken record again) having to recognize what a properly-formatted manuscript should look like.

Actually, the aspiring writer’s learning curve is often not dissimilar to Millicent’s: no one tumbles out of the womb already familiar with the rules of manuscript formatting. (Okay, so I practically was, growing up around so many authors, but I’m a rare exception.) Like Millicent, most of us learn the ropes only through reading a great deal.

She has the advantage over us, though: she gets to read books in manuscript form, and most aspiring writers, especially at the beginning of their journeys to publication, read only books. So what writers tend to produce in their early submissions are essentially imitations of books.

The problem is, the format of the two is, as I believe that I have pointed out, oh, several hundred times before in this very forum, quite different — and not, as some of you may have been muttering in the darkness of your solitary studios throughout this series, merely because esoteric rules render it more difficult for new writers to break into the biz.

As a matter of fact, there are many reasons that a manuscript in book format would be hard for an agent or editor to handle. For starters, published books are printed on both sides of the page, manuscripts on one.

Why the difference, in these days of declining tree populations and editors huffily informing writers at conferences that paper is expensive? Simple: it’s easier to edit that way.

Which is why, even in these days of widely available word processors, scads of professional editing is still done by hand.

Again, why? Well, it’s a mite hard to give trenchant feedback while traveling in a crowded subway car if you have to maneuver a laptop (or, as I can tell you from personal experience this very minute, while squished between burly, restless fellow passengers on a plane).

Also, many agencies remain far too virus-fearful to allow their employees solicit attachments from writers who aren’t already clients. (Those who do generally have a policy that forbids the opening of unsolicited attachments, FYI.) Even in agencies that have caved in to new technology sufficiently to send their member agents on long airplane flights to writers’ conferences armed with a Kindle with 17 manuscripts on it, hand-written marginalia is still the norm, even if it means scanning hand-proofed pages and e-mailing them back to the author.

Ultimately, most editors edit in hard copy because they prefer it. The human eye is, of course, to blame for this: reading comprehension drops by about 70% when the material is presented on a computer screen; the eye tends to skim.

Which is why — you can hear this coming, can’t you? — a wise writer always reads her ENTIRE manuscript IN HARD COPY before submitting it to anyone even vaguely affiliated with the publishing industry. It’s much, much easier to catch typos and logic problems that way.

While you’ve got your hymnals out, long-time readers, let’s continue with the liturgy: manuscripts should also be typed (don’t laugh; it’s not unheard-of for diagrams to be hand-drawn, hand-number, or for late-caught typos to be corrected in pen), double-spaced, and have 1-inch margins all the way around.

Time to see why, from an editing point of view.

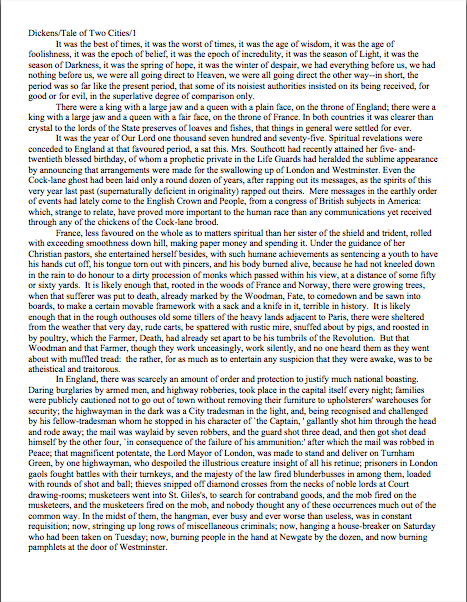

You had hoped that I’d gone too far afield to get back to the topic at hand, didn’t you? Not a chance. Let’s call upon our old friend Charles Dickens again to see what a page of a manuscript should look like:

Nice and easy to read, isn’t it? (If it’s too small to read easily on your browser, try double-clicking on the image.)

To give you some idea of just how difficult — or even impossible — it would be to hand-edit a manuscript that was NOT double-spaced or had smaller margins, take a gander at this little monstrosity:

I believe the proper term for this is reader-hostile. Even an unusually patient and literature-loving Millicent would reject a submission like this immediately, without reading so much as a word.

Were there a few spit-takes out there during that last sentence? “My goodness, Anne,” those of you who are wiping coffee, tea, or the beverage of your choice off your incredulous faces sputter, “why would any sane person consider it THAT serious an offense? It is, after all, precisely the same writing.”

Well, think about it: even with nice, empty page backs upon which to scrawl copy edits, trying to cram spelling or grammatical changes between those lines would be well-nigh impossible. Knowing that, Millicent would never dream of passing such a manuscript along to the agent who employs her; to do so would be to invite a stern and probably lengthy lecture on the vicissitudes of the editorial life.

She wasn’t born yesterday, you know. She’s SMART.

Don’t tempt her just to reject it unread — and don’t even consider, I beg of you, providing the same temptation to a contest judge. Given the sheer volume of submissions the average Millicent reads, she’s not all that likely to resist — and the contest judge will be specifically instructed not to resist at all.

Yes, really. Even if the sum total of the provocation consists of a manuscript that’s shrunk to, say, 95% of the usual size, it’s likely to get knocked out of the running on sight.

Some of you are blushing, aren’t you? Perhaps some past contest entrants and submitters who wanted to squeeze in a particularly exciting scene before the end of those requested 50 pages?

No? Let me fill you in on a much-deplored practice, then: faced with a hard-and-fast page limit for submission, some wily writers will shrink the font or the margins, to shoehorn a few more words onto each page. After all, the logic runs, who is going to notice a tenth of an inch sliced off a left or right margin, or notice that the typeface is a trifle smaller than usual?

Millicent will notice, that’s who, and practically instantly. As will any reasonably experienced contest judge; after hours on end of reading 12-point type within 1-inch margins, a reader develops a visceral sense of when something is off.

Don’t believe me? Go back and study today’s first example, the correctly formatted average page. Then take a gander at this:

I shaved only one-tenth of an inch off each margin and shrunk the text by 5% — far, far less than most fudgers attempt. Admit it: you can tell it’s different, can’t you, even without whipping out a ruler?

So could a professional reader. And let me tell you, neither the Millicents of this world nor the contest judges tend to appreciate attempts to trick them into extraneous reading. Next!

The same principle applies, incidentally, to query letters: often, aspiring writers, despairing of fitting a coherent summary of their books within the standard single page, will shrink the margins or typeface.

Trust me, someone who reads queries all day, every day, will be able to tell. (And if you would like to see precisely why, please check out the posts under the QUERY LETTERS ILLUSTRATED category on the list at right.)

The other commonly-fudged spacing technique involves skipping only one space after periods and colons, rather than the grammatically-requisite two spaces. Frequently, writers won’t even realize that this IS fudging: as readers have pointed out VEHEMENTLY in the comments whenever I have talked about this in the past, ever since published books began omitting these spaces in order to save paper, there are plenty of folks out there who insist that skipping the extra space in manuscripts is obsolete. Frequently, the proponents will insist that manuscripts that include the space look old-fashioned to agents and editors.

And I’m not going to lie to you here: to the agents who prefer this format, it is going to look old-fashioned. Sorry. Fortunately, however, the relatively few (and usually younger) agents who prefer the single-space option are usually exceedingly vocal about it, so aspiring writers seeking to submit to them usually don’t have a particularly hard time finding out about their preference.

How can you spot such an agent in the wild? She’s usually the one on the conference dais insisting that absolutely NOBODY accepts manuscripts with two spaces after periods and colons anymore.

Which just isn’t true; the language hasn’t actually changed, and the old-fashioned agents and editors who are aware of that tend to feel rather strongly about their preference, too. And those are the ones who will actually make the writers who work with them go through their manuscripts and add back that second space.

Yes, really — and yes, recently. One doesn’t hear of it happening the other way around.If the agent you have set your heart upon has not gone on the record about it, then, it is generally safer to go with the 2-space option.

I sense a bit of dissention out there, do I not? Perhaps a few faint whispers about how this view is old-fashioned, and is likely to be looked down upon as such?

Well, guess what, cookie — standard manuscript format IS old-fashioned, by definition; that fact doesn’t seem to stop most of the currently-published authors of the English-speaking world from using it. In fact, in all of my years writing and editing, I have never — not once — seen an already agented manuscript rejected or even criticized for including the two spaces that English prose requires after a period or colon.

I have, however, heard endless complaint from professional readers — myself included — about those second spaces being omitted. Care to guess why?

Reward yourself with a virtual candy cane if you said that cutting those spaces throws off word count estimation; the industry estimates assume those doubled spaces. (If you don’t know how and why word count is tallied, please see the WORD COUNT category on the archive list at right.)

And give yourself twelve reindeer if you also suggested that omitting them renders a manuscript harder to hand-edit. We all know the lecture Millicent is likely to get if she forgets about that, right?

Again, a pro isn’t going to have to look very hard at a space-deprived page to catch on that there’s something fishy going on. Since Dickens was so fond of half-page sentences, the examples I’ve been using above won’t illustrate this point very well, so (reaching blindly into the depths of the bookshelf next to my computer), let’s take a random page out of Elizabeth Von Arnim’s VERA:

There are 310 words on this page; I wasn’t kidding the other day about how far off the standard word count estimations were, obviously. Now cast your eye over the same text improperly formatted:

Doesn’t look much different to the naked eye, does it? The word count is only slightly lower on this version of this page — 295 words — but enough to make quite a difference over the course of an entire manuscript.

So I see some hands shooting up out there? “But Anne,” I hear some sharp-eyed readers exclaim, “wasn’t the word count lower because there was an ENTIRE LINE missing from the second version?”

Well spotted, criers-out: the natural tendency of omitting the second spaces would be to include MORE words per page, not less. But not spacing properly between sentences was not the only deviation from standard format here; Millicent, I assure you, would have caught two others.

I tossed a curve ball in here, to make sure you were reading as closely as she was. Wild guesses? Anyone? Anyone?

The error that chopped the word count was a pretty innocent one, almost always done unconsciously: the writer did not turn off the widow/orphan control, found in Word under FORMAT/PARAGRAPH/LINE AND PAGE BREAKS. This insidious little function, the default unless one changes it, prevents single lines of multi-line paragraphs from getting stranded on either the bottom of one page of the top of the next.

As you may see, keeping this function operational results in an uneven number of lines per page. Which, over the course of an entire manuscript, is going to do some serious damage to the word count.

The other problem — and frankly, the one that would have irritated a contest judge far more than Millicent — was on the last line of the page: using an emdash (“But—”) instead of a doubled dash. Here again, we see that the standards that apply to printed books are not proper for manuscripts.

Which brings me back to today’s moral: just because a particular piece of formatting looks right to those of us who have been reading books since we were three doesn’t mean that it is correct in a MANUSCRIPT.

Millicent reads manuscripts all day; contest judges read entries for hours at a time. After a while, a formatting issue that might well not even catch a lay reader’s attention can begin to seem gargantuan.

As I have perhaps pointed out once or twice throughout this series, if the writing is good, it deserves to be free of distracting formatting choices. You want agents, editors, and contest judges to be muttering, “Wow, this is good,” over your manuscript, not “Oh, God, he doesn’t know the rules about dashes,” don’t you?

Spare Millicent the chagrin, please; both you and she will be the happier for it. Believe me, she could use a brilliantly-written, impeccably-formatted submission to brighten her Dickensian day.

I shall have to sign off now, because the fellow sitting next to yours truly spilled his glass of water onto the keyboard, and I now do not appear to be able to use either the letter that follows L in the alphabet or the se()icolon. If I can get ()y co()puter fixed on the road, ()ore show-and-tell follows next time. If not, well, it was ti()e for another guest post on subtle censorship, anyway, right?

Think good thoughts for ()y ()issing letters() swift return — oh, God, the U now needs to be hit three ti()es in order to show up on the screen –and, of course, keep up the good work!

Dear Anne,

How should an author introduce dates, days of the week etc, to his/her mansucript. Should they always appear at the start of a chapter? Should they appear at a section break, and if so, when?

I’m not sure I entirely understand the question, Pete. There are many, many manuscripts that simply incorporate time markers into the narrative itself, as in Ambrose Bierce’s, “Early one June morning in 1872 I killed my father — an act which made a deep impression upon me at the time.”

In fact, that’s the usual way to alert the reader to when a story is taking place. That being the case, there couldn’t possibly be a rule that states positively where in a manuscript that information should appear. It’s a matter of style, not formatting.

Unless you mean the device of essentially entitling a chapter or section with time indicators on the order of October, 1947? It’s not considered the most graceful means of conveying dates, but it’s certainly acceptable in most genres.

The proper way to format a date introduced in this manner is to treat the information precisely as if it were the title of the chapter. Format it accordingly. If the chapter also has a title, treat the date as the subtitle.

If you’re prone to introduce this information in the middle of a chapter (and, again, don’t feel that you can just work it into the narrative without its seeming intrusive), use the date as the title of a section. You’ll find examples of section headings in the last post in this series.

But I suspect that this doesn’t really answer your question, does it?