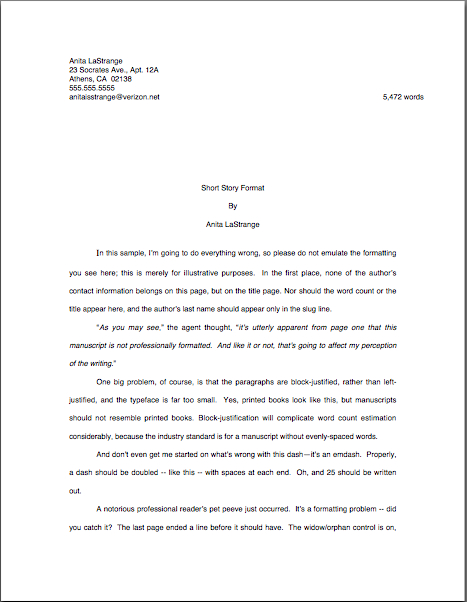

What’s that pile of jagged rubble, you ask, and why am I asking you to contemplate it? Is it a close-up of a stepped-upon family of crabs, or perhaps the aftermath of something extremely large having been dropped from a plane? No such luck, my friends: this is my flower and herb garden, immediately after those nice men who came to solve the drainage problem in the basement stopped destroying all life forms unwise enough to be planted in their path.

Or, to be precise, my garden is under what you see; the backhoe is relaxing after its Herculean labors in concealing it from human eyes. Originally, there was a full-grown rosebush compressed between the top two levels of slab, sticking out sideways with its tender new leaves reaching desperately toward the sky. However, once I came running out with my camera, the workers hurriedly whisked most of dead and dying plant life out of shot.

I’m pretty annoyed about the demise of my bulbs — silly me, I had thought that something growing two feet tall with a flower on one end of it would have self-evidently been something to save, but evidently, that’s a matter of debate — but even at the zenith of my pique, I couldn’t help but gasp at how apt a metaphor it was for this week’s topic.

After all, isn’t it one of the great rules of creation that it usually involves some destruction?

Just as (my SO assures me) the construction of a new, improved, and in every way far more admirable backyard patio and garden required ripping up the old concrete patio and dumping the shards of its dislodged corpse on top of every green and growing thing within a hundred yards, often, building a revised draft of an already-written manuscript entails ripping out some of the foundation, to clear space for new reinforcement.

Unlike the perpetrators of many other structures, the writer of a manuscript-under-construction is often present when critics are hacking away at the second floor solarium and that view-blocking cypress tree just outside the library, unfortunately. And that can be trying to even the calmest temperament.

You know the situations I’m talking about, right? Writers’ groups. Face-to-face pitching sessions, especially those at conferences where the pitchees have ostensibly read an excerpt from the work being pitched. Lunch or a phone call with one’s agent or editor — or with some generous soul who has agreed to be a first reader for your manuscript.

Like it or not, while querying and submission usually generate written responses, ideally suited for psyche-clearing tantrum-throwing in the privacy of one’s home, getting concrete feedback on your work often requires your physical — or at least auditory — attendance. Pulling this off well is a matter of will — and of practice.

We’re all familiar with what happens when a writer doesn’t pull it off well, right? As we saw with this weekend’s exemplars, all too often, writers respond with defensiveness (“What do you mean, there’s something wrong with my manuscript, Candace?”), anger (“What kind of a fool are you to think you have the right to criticize my work, Jerome?”), or endless explanation about why the manuscript positively needs to remain precisely the way it currently is (“Clearly, Ted, you’re not understanding what’s going on, so let me proceed on the assumption that what’s on the page is far less important than my intention in placing it there.”)

None of these responses is constructive, and all are as likely to prevent good feedback from sinking into the writerly noggin as to ward off misguided advice. Still worse, they tend to discourage honesty in future feedback.

The funny thing is, most of the time, writers who embrace these tactics DO want feedback on their work — but they make the fundamental mistake of confusing the time and energy they’ve expended with the quality or clarity of the writing. In other words, they respond as though the industry graded manuscripts for effort, not for what actually ends up on the page.

Which, as I believe I have already mentioned in this series, is backward, logically speaking. If it’s not on the page, it doesn’t count, as far as agents, editors, and contest judges are concerned — and, really, most bookstore browsers feel the same way, don’t they? Who walks into Borders thinking, “Gee, where can I find a book upon which the author lavished care and attention?” rather than, “Hey, where can I find a great read?”

So when an agent encounters a new client whose first response to a change request is defensive, or an editor finds that her brilliant new discovery apparently enjoys endless discussion over the smallest prospective change, they tend not to be too sympathetic.

And that’s a shame, really, because very, very often, what the author is actually saying is, “Hey, I put a lot of work into this. Can’t we stop and recognize that before ripping it apart? Or do you really mean that you don’t think I have talent?”

We sometimes see a similar reaction, interestingly enough, in authors on their first few book tours. “What do you mean, you would have ended the book differently?” they demand of some trembling soul who wanted only to say something intelligent while having her copy of the book signed. “Everyone’s a critic?”

In the age of the Internet, just how often do you think an author needs to snap at a well-meaning fan before he gains a reputation for being nasty at book readings?

Because this tendency to knee-jerk defensiveness is extremely common, I’m a big fan of aspiring writers pulling the pin on the criticism grenade BEFORE they are under professional scrutiny. Critique groups can be tremendously helpful in learning to respond well to commentary, as can working with a freelance editor. Entering contests that provide feedback, and even exchanging manuscripts with a helpful friend can be marvelous ways to learn to subvert the instinctive negative reaction.

In short, why not test your capacity for critique first in a venue where a momentary lapse could not conceivably to cost you a representation or book contract — or readers?

Of course, I’m not going to send you into a high-powered writers’ group entirely unarmed; like our exemplar Harriet, writers who walk into their first face-to-face critique not knowing what to expect are often frightened away.

Never fear: being the preparation-oriented self you all know and love, I have come up with a few strategies for handling it with aplomb. These are not the only tools you could use in this situation — and those of you who are critique veterans, please chime in with what has worked for you — but armed with these techniques, no writer need be afraid of making a fool of himself by over-reacting to well-meant feedback.

Note, please, that these techniques do not depend upon how good the feedback is; they will help you keep a high chin, straight face, and positive attitude even if it’s dreadful. (Don’t worry — I shall be talking about how to deal with unhelpful feedback later in the week.)

Ready? Here we go.

1. Walk in with a couple of specific questions you would like your critiquers to answer.

Those of you who survived last December-January’s series of posts on how to seek out useful feedback (gathered under the unambiguous title GETTING GOOD FEEDBACK in the category list at right) might recognize this one. In my experience, the level of critique is almost always improved if the writer gives the reader a bit of advance warning about what he’d like to discuss.

Even if the structure of the feedback situation prevents a pre-reading heads-up, it’s still an excellent idea to come into a face-to-face critique (a conference meeting with an agent who has read your first chapter, for instance) with two or three concrete questions you would like answered about your work.

Why? Well, to be blunt about it, it helps give you some control of a situation that can be overwhelming — and it’s can be a positive boon if you should happen to find your work being critiqued by someone genuinely nasty. Trust me, you’ll be far, far happier if you have prepared yourself to say, “What did you think of the pacing of the opening?” rather than finding yourself stammering, “What do you mean, you didn’t like it?”

But there are far more positive reasons to go this route. First, it’s a courtesy to your critiquer: it demonstrates that you value his opinion. Or, perhaps more importantly for dealing with an agent or editor, it makes it APPARENT that you do. (Whether you actually value this yahoo’s opinion or not is, of course, nobody’s business but you and your personal Jim’ny Cricket.)

It also forces you to take a critical look at your own work, to determine where it might have some weaknesses. That is a HUGE advantage walking into a feedback situation, because it enables a writer to open her mind to other perspectives, rather than feeling that she needs to defend what she’s done.

Remember: the purpose of manuscript critique is to make it better, not to punish past errors. Keep your eye on the prize.

A couple of questions to get you started: if you write comedy, consider asking if there was anyplace in the manuscript that made the critiquer laugh out loud — or a bit that didn’t quite work; if you write memoir, ask if every scene seemed plausible, or if the ratio of scene to narrative seemed right; if you write fiction, also ask if every scene seemed plausible, or if the protagonist seemed likable or interesting enough to follow throughout the entire book.

Yes, you DO want to be that concrete, if the feedback is going to help you revise.

2. Bear in mind that today is not necessarily the best day to respond to what you’re hearing.

In other words, consider not saying anything when you receive feedback. Just listen carefully, nodding occasionally as a courtesy to the speaker, trying to absorb what will be most useful to you and the manuscript.

This strategy often surprises writers, but there is no rule that requires us to have a witty riposte ready the instant after a first reader has just pointed out a fundamental flaw — or even a minor one — in our manuscripts. Feedback is not, after all, an invitation to argument, but a set of specific suggestions about how to improve a book.

Silence is a perfectly acceptable response — and if you’re new to face-to-face critique, it is often downright preferable. To illustrate why, I’m going to jump out of the realm of art for the moment and into the murky waters of group psychology.

In the Northern California of my childhood, a form of group interaction known as an encounter group was fleetingly popular. A bunch of individuals got together, picked (I almost said victim) one member to be the subject, and talked exclusively about that person for a set period of time, to give the subject what was supposed to be an unprecedented view of how he appeared to others. Two rules prevailed: everyone was supposed to be absolutely honest, and the subject was not allowed to speak until the session was over.

I just felt half of you recoil in horror, didn’t I? Well, yes, it could be mighty intense, but since everyone in the group was going to be the subject eventually, the idea was that everyone would be equally vulnerable — and that by preventing the subject from voicing an instantaneous defensive reaction, people could say precisely what they thought without fear of interruption.

The idea of exchanging manuscripts for critique, as opposed to personalities, suddenly seems a bit less threatening, doesn’t it?

That’s not why I brought up encounter groups, however: in the face of feedback, it is usually far easier to hear what others are saying if part of your brain isn’t spinning constantly, trying to come up with a pithy comment in response, if not something so devastating that it will be passed down to future generations as a proverb. (Oh, as if writers aren’t prone to doing that.)

Try just listening. You may be surprised at how much stress it leeches from the critique encounter.

3. Take good notes.

This one is in response to all of you who were picturing yourself just sitting there fidgeting while others told you how to improve your work. You’re going to be keeping yourself occupied, I assure you.

Bring a pad of paper and writing implement. Apply the latter to the former liberally.

Do I hear some shy souls shuffling their feet out there, working up nerve to ask a question? “But Anne,” these timid writers say, “isn’t it a bit rude to be scribbling while someone else is speaking? Won’t they assume that I’m not paying attention, but have started doodling out of boredom?”

Actually, a feedback-giver usually finds it flattering when a writer keeps jotting things down, for the same reason that a lecturer finds it encouraging when her students seem to be taking copious notes: it implies that the scribbler respects what the speaker is saying enough to want to remember it.

The higher her educational level, incidentally, the more likely she is to be pleased. In fact, when academics get together for symposia, it’s almost unheard-of for a lecturer NOT to take notes during the question-and-answer period. While the questioner is asking. Not only is this not considered impolite — it’s regarded as a way that the lecturer conveys to the questioner that she’s asked a good question.

So feel free to write down what your feedback-giver says about your work — yes, even if the critiquer happens to be the editor to whom you’ve just pitched your book project. Write down any follow-up questions you might have. Write down any inspirations you might have for applying the feedback to the manuscript.

Why? Because even the best feedback isn’t going to be very useful if you can’t remember it tomorrow, is it?

My, that’s a lot to digest in one post, isn’t it? More strategic tips follow tomorrow, of course, but just before we end for today, take a moment to pat yourself on the back for being open to accepting feedback on your baby at all. By being brave enough to allow others to take a long, hard look at your writing AND developing the skills to listen to their honest responses, you’re taking an important step toward approaching the job of writing like a professional.

And if the prospect of soliciting feedback still feels like someone’s about to take a backhoe to your beloved backyard garden, well, today of all days, I sympathize. Necessary renovation can have some pretty disorienting short-term side effects. But isn’t having to replant the bulbs worth it if the basement is no longer going to fill up with water when it rains?

Give it some thought — and keep up the good work!