I meant to post yesterday, honestly; blame my physical therapist’s fondness for crying out, “Just lean on your hands for another few minutes while we try X…” I use those hands for other things, as it turns out. I even had this half-written before PT yesterday, but all of my hand and wrist strength had been used up for the day.

I’ve said it before, and I’ll no doubt say it again: life is no respecter of deadlines.

As we’ve been working our way through Synopsispalooza, I’ve been worrying about something over and above my aching wrists: has my advice that virtually any aspiring writer will be better off sitting down to construct a winning synopsis substantially before s/he is likely to need to produce one coming across as a trifle callous, as if I were laboring under the impression that the average aspiring writer doesn’t already have difficulty carving out time in a busy day to write at all? Why, some of you may well be wondering, would I suggest that you should take on more work — and such distasteful work at that?

I assure you, I have been suggesting this precisely because I am sympathetic to your plight. I completely understand why aspiring writers so often push producing one to the last possible nanosecond before it is needed: it genuinely is a pain to summarize the high points of a plot or argument in a concise-yet-detail-rich form.

Honestly, I get it. The newer a writer is to the task, the more impossible — and unreasonable — it seems.

And frankly, aspiring writers have a pretty good reason to feel that way about constructing synopses: it is such a different task than writing a book, involving skills widely removed from observing a telling moment in exquisite specificity or depicting a real-life situation with verve and insight, the expectation that any good book writer should be able to produce a great synopsis off the cuff actually isn’t entirely reasonable.

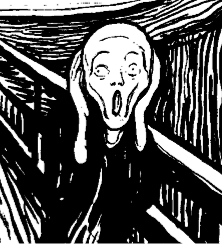

So it’s probably not utterly surprising that the very prospect of pulling one together can leave a talented writer feeling like this:

Rather than the way we feel when we polish off a truly stellar piece of writing, which is a bit more like this:

There’s just no getting around it: synopsis-writing, like pitch- and query-writing, is not particularly soul-satisfying. Nor is it likely to yield sentences and paragraphs that will be making readers weep a hundred years from now — fortunate, perhaps, because literally no one outside of an agency, publishing house, or contest-judging bee is ever going to see the darned thing. Yet since we cannot change the industry’s demand for them, all we writers can do is work on the supply end: by taking control of WHEN we produce our synopses, we can make the generation process less painful and generally improve the results.

Okay, so these may not sound like the best conceivable motivations for taking a few days out of your hard-won writing time to pull together a document that’s never going to be published — and to do so before you absolutely have to do it. Unless you happen to be a masochist who just adores wailing under time pressure, though, procrastinating about producing one is an exceedingly bad idea.

But as of today, I’m no longer going to ask you to take my word for that. For those of you who are still resistant to the idea of writing one before you are specifically asked for it I have two more inducements to offer you today.

First — and this is a big one – taking the time to work on a synopsis BEFORE you have an actual conversation with an agent (either post-submission or at a conference) is going to make it easier for you to talk about your book professionally.

Don’t sneeze at that advantage, perennial queriers — it’s extremely important for conference-goers, e-mail queriers, and pretty much everyone who is ever going to be trying to convince someone in the publishing industry to take an interest in a manuscript, because (brace yourselves) the prevailing assumption amongst the pros is that a writer who cannot talk about her work professionally probably is not going to produce a professional-quality manuscript.

I know, I know — from a writer’s point of view, this doesn’t make a whole lot of sense: we all know (or are) shy-but-brilliant writers who would rather scarf down cups of broken glass than give a verbal pitch, yet can produce absolute magic on the page. Unfortunately, in contexts where such discussion is warranted, these gifted recluses are out of luck.

Why? Well, it’s sort of like the logic underlying querying: evaluating a 400-page manuscript based solely upon a single-page query letter — or, even more common, upon the descriptive paragraph in that query — is predicated upon the assumption that any gifted writer must be able to write marketing copy and lyrical prose equally well. (Cough, cough.) Similarly, conference pitching assumes that the basic skills an agent must have in order to sell books successfully — an ability to boil down a story or argument to its most basic elements while still making it sound fascinating, a knack for figuring out how it would fit into the current market, the knowledge to determine who would be the most receptive audience, editorial and reader both, for such a book, the bravery to tell someone in a position to do something about it — are lurking in the psyche of your garden-variety brilliant writer as well.

Come to think of it, querying and synopsizing effectively require most of those skills as well, don’t they? Particularly synopsizing, if you think about it like a marketer, rather than like a writer.

And yes, you should try to do that from time to time: contrary to popular opinion amongst aspiring writers, being market-savvy does not necessarily mean compromising one’s artistic vision or selling out. As any working artist could tell you, one can be a perfectly good artist and still present one’s work well for marketing purposes. Refusing to learn professional presentation skills does not improve one’s art one jot; all it does is make it harder to sell that art.

So force yourself to think like a marketer for a second, rather than the author of that 380-page novel: if you were the book’s agent, how would you describe it to an editor? Perhaps like this:

(1) introduce the major characters and premise,

(2) demonstrate the primary conflict(s),

(3) show what’s at stake for the protagonist, and

(4) ideally, give some indication of the tone and voice of the book.

(5) show the primary story arc through BRIEF descriptions of the most important scenes.

(6) show how the plot’s primary conflict is resolved or what the result of adopting the book’s argument would be.

Or, if you were the agent for your nonfiction book, you might go about it like this:

(1) present the problem or question the book will address in a way that makes it seem fascinating even to those not intimately familiar with the subject matter,

(2) demonstrate why readers should care enough about the problem or question to want to read about it,

(3) mention any large group of people or organization who might already be working on this problem or question, to demonstrate already-existing public interest in the subject,

(4) give some indication of how you intend to prove your case, showing the argument in some detail and saying what kind of proof you will be offering in support of your points,

(5) demonstrate why the book will appeal to a large enough market niche to make publishing it worthwhile (again, ideally, backed up with statistics), and

(6) show beyond any reasonable question that you are the best-qualified person in the known universe to write the book.

In short, you would be describing your book in professional terms, rather than trying to summarize the entire book in 1-5 pages. In fact, try thinking of your synopsis as the book’s first agent: its role is not to reproduce the experience of reading your manuscript, but to convince people in the publishing industry to read it.

Tell me: does thinking of the pesky thing in those terms make it seem more or less intimidating to write?

Although it may feel like the former, in the long term, taking the time to do this well usually helps a writer feel less intimidated down the line. Investing some serious time in developing a solid, professional-quality synopsis can be very, very helpful in this respect. The discipline required to produce it forces you to think of your baby as a marketable product, as well as a piece of complex art and physical proof that you have locked yourself away from your kith and kin for endless hours, creating.

Not only will it be easier for you to sit down and write a synopsis for your next book (and the one after that), but by training yourself not to answer the question, “So what do you write?” with a short, pithy, market-oriented overview of the plot or argument, you are going to come across to others as much more serious about your writing than if you embrace the usual response of, “Well, um, it’s sort of autobiographical…”

Again, that progress is nothing at which to be sneezing. An aspiring writer who has learned to discuss his work professionally is usually better able to get folks in the industry to sit down and read it. That’s not a value judgment — it’s a fact.

Half of you are shaking your heads in resentful disbelief, aren’t you? “But Anne,” those of you annoyed by the brevity of a requested synopsis point out, “you keep saying that every syllable an aspiring writer sends to an agency is a writing sample. So how can I NOT think of the 3-page synopsis they want me to send as a super-compressed version of my book? Let me be all stressed out over trying to fit 100 pages into a paragraph or two, already.”

I can tell you how: because you’ll drive yourself crazy if you think of it that way. The purpose of a synopsis is not to summarize the entire book; it is to give a swift overview of its high points. Thus, the synopsizer’s problem is not compression — it’s selection.

Does the sound of a thousand pairs of eyebrows crashing into hairlines mean that some of you had never thought of it that way before? Cast your eyes back over those lists of what is supposed to be in a professional synopsis: do any of those steps actually ask you to summarize the book?

No, they are asking you to hit the high points — but to present those high points like a readable story or single-line argument.

Don’t get too upset if you hadn’t thought of it that way before. Even writers who are absolutely desperate to sell their first books tend to forget that it is a product intended for a specific market. As I have mentioned earlier in this series, in the throes of resenting the necessity of producing a query letter and synopsis, it is genuinely difficult NOT to grumble about having to simplify a beautifully complicated plot, set of characters, and/or argument.

But think about it for a second: any agent who signs you is going to have to be able to rattle off the book’s high points in order to market it to editors. So is any editor who falls in love with it, in order to pitch it to an editorial committee.

See why they might want to have a synopsis by their sides? This is not a pointless hoop through which agents, editors, and contest rule-mongers force aspiring writers to jump in order to test their fortitude; a synopsis is a professional requirement, necessary for any of these people to help you bring your writing to your future reading public.

You’re feeling just the teensiest bit better about having to write the darned thing, aren’t you?

Here’s another good reason to invest the time: by having labored to reduce your marvelously complex story or argument to its basic elements, you will be far less likely to succumb to that perennial bugbear of pitchers, the Pitch that Would Not Die.

Those of you who have pitched at conferences know what I’m talking about, right? Everyone who has hung out with either pitchers or pitch-hearing agents has heard at least one horror story about a pitch that went on for an hour, because the author did not have the vaguest conception what was and was not important to emphasize in his plot summary.

Trust me, you do not want to be remembered for that. Your manuscript has many, many other high points, doesn’t it?

For those of you who haven’t yet found yourself floundering for words in front of an agent or editor, allow me to warn you: the unprepared pitcher almost always runs long. When you are signed up for a 10-minute pitch meeting, you really do need to be able to summarize your book within just a few minutes — harder than it sounds! — so you have time to talk about other matters.

You know, mundane little details, such as whether the agent wants to read the book in question.

Contrary to the prevailing writerly wisdom that dictates that verbal pitching and writing are animals of very different stripes, spending some serious time polishing your synopsis is great preparation for pitching. Even the most devoted enemy of brevity will find it easier to chat about the main thrust of a book if he’s already figured out what it is.

Stop laughing — I have been to a seemingly endless array of writers’ conferences over the years, and let me tell you, I’ve never attended one that didn’t attract at least a handful of aspiring writers who seemed not to be able to tell anyone else what their books were about.

Which, in case you were wondering, is the origin of that hoary old industry chestnut:

Agent: So, what’s your book about?

Writer: About 900 pages.

The third inducement: a well-crafted synopsis is something of a rarity, so if you can produce one as a follow-up to a good meeting at a conference, or to tuck into your submission packet with your first 50 pages, or to send off with your query packet, you will look like a star, comparatively speaking.

You would be astonished (at least I hope you would) at how often an otherwise well-written submission or query letter is accompanied by a synopsis obviously dashed off in the ten minutes prior to the post office’s closing, as though the writing quality, clarity, and organization of it weren’t to be evaluated at all. I don’t think that sheer deadline panic accounts for the pervasiveness of the disorganized synopsis; I suspect lack of preparation.

Hmm, wasn’t someone just talking about unprepared pitchers always going long?

I also suspect resentment. I’ve met countless writers who don’t really understand why the synopsis is necessary at all; to them, it’s just busywork that agents request of aspiring writers, a meaningless hoop through which they must jump in order to seek representation.

No wonder they hate it; they regard it as a minor species of bullying. But we all know better than that now, right?

All too often, the it’s-just-a-hoop mentality produces a synopsis that gives the impression not that the writer is genuinely excited about this book and eager to market it, but rather that he is deeply and justifiably angry that it needed to be written at all.

And that’s a problem, because to an experienced eye, writerly resentment shows up beautifully against the backdrop of a synopsis. It practically oozes off the page.

Unfortunately, the peevish synopsis is the norm, not the exception; as any Millicent who screens queries and submissions would be more than happy to tell you, it’s as though half the synopsis-writers out there believe they’re entering their work in an anti-charm contest. The VAST majority of novel synopses simply scream that their authors regarded the writing of them as tiresome busywork instituted by the industry to satisfy some sick, sadistic whim prevalent amongst agents to see aspiring writers suffer.

(You’re chortling at this attitude by this point in the post, aren’t you, even if you were one of the many who believed it, say, yesterday? If not, you might want to go back and reread that bit about why the agent of your dreams actually does need you to provide her with a synopsis. But back to the resentment already in progress.)

Frustrated by what appears to be an arbitrary requirement, many writers just do the bare minimum they believe is required, totally eschewing anything that might remotely be considered style. Or, even more commonly, they procrastinate about doing it at all until the last possible nanosecond, and end up throwing together a synopsis in a fatal rush and shove it into an envelope, hoping that no one will pay much attention to it.

It’s the query letter and the manuscript that count, right?

Wrong. In case you thought I was joking the other 47 times I have mentioned it over the last couple of weeks, EVERYTHING you submit to an agent or editor is a writing sample.

If you can’t remember that full-time, have it tattooed on the back of your hand. It honestly is that important to your querying and submission success.

While frustration is certainly understandable, it’s self-defeating to treat the synopsis as unimportant or to crank it out in a last-minute frenzy. Find a more constructive outlet for your annoyance — and make sure that every page you submit represents your best writing.

Realistically, it’s not going to help your book’s progress one iota to engage in passive-aggressive blaming of any particular agent or editor. It’s even less sensible to resent their Millicents. They did not make the rules, by and large.

And even if they did, let’s face it — in real life, almost nobody is actually brave enough to say to an agent or editor, “No, you can’t have a synopsis, you lazy so-and-so. Read the whole darned book, if you liked my pitch or query, because the only way you’re going to find out if I can write is to READ MY WRITING! AAAAAAAAH!”

Okay, so it’s mighty satisfying to contemplate saying it. Picture it as vividly as you can, then move on.

I’m quite serious about this. My mental health assignment for you while working on the synopsis: once an hour, picture the nastiest, most aloof agent in the world, and mentally bellow your frustrations at him at length. Be as specific as possible about your complaints, but try not to repeat yourself; the goal here is to touch upon every scintilla of resentment lodged in the writing part of your brain.

Then find the nearest mirror, gaze into it, and tell yourself to get back to work, because you want to get published. Your professional reputation — yes, and your ability to market your writing successfully — is at stake.

I know, the exercise sounds silly, but it will make you feel better to do it, I promise. Far better that your neighbors hear you screaming about how hard it all is than that your resentment find its way into your synopsis. Or your query letter. Or even into your verbal pitch.

Yes, I’ve seen all three happen — but I’ve never seen it work to the venting writer’s advantage. I’ll spare you the details, because, trust me, these were not pretty incidents.

Next time, I shall delve very specifically into the knotty issue of how a synopsis folded up behind a cold query letter might differ from one that is destined to sit underneath a partial manuscript. In the meantime, try to indulge in primal screaming only when nobody else is around, and keep up the good work!