I’ve taken the last couple of days off, not so much in recognition of the holiday associated with the Furtive Non-Denominational Gift-Giver (a.k.a. Santa) as in response to the fact that in these dark days, long-term illness is apparently not generally regarded as sufficient excuse to absent oneself from festivities. At least, not if one has established a reputation as a good cook.

In other words, there’s no place like home for the hollandaise. (If you decided to co-opt that groaner, please give me credit. I’m rather fond of it.)

But now I’m back in the saddle, eager to polish off our special holiday treat, a discussion about self-publishing with two authors who have taken the plunge this year, fellow blogger and memoirist Beren deMotier and novelist Mary Hutchings Reed. Today, we’re going to dig our teeth into the meaty issues of inspiration, promotion, and just what happens after an author commits to bringing out her own work.

So please join me in welcoming back both. To begin, let’s remind ourselves what they have published and where an interested party might conceivably go to buy it.

Mary Hutchings Reed, if you’ll recall, is the author of COURTING KATHLEEN HANNIGAN, which is being described as the ONE L for women lawyers. It is available on Amazon or directly from the author herself on her website.

Mary Hutchings Reed, if you’ll recall, is the author of COURTING KATHLEEN HANNIGAN, which is being described as the ONE L for women lawyers. It is available on Amazon or directly from the author herself on her website.

Courting Kathleen Hannigan tells the story of an ambitious woman lawyer, one of the first to join a male-dominated national law firm in the late seventies, whose rise to the top is threatened by a sex discrimination suit brought against the firm by a junior woman lawyer who is passed over for partnership because she doesn’t wear make-up or jewelry. When Kathleen Hannigan is called to testify, she is faced with a choice between her feminist principles and her own career success. Courting Kathleen Hannigan is a story for women and minorities everywhere who are curious about the social history of women in law, business and the professions, institutional firm cultures, and the sexual politics of businesses and law firms.

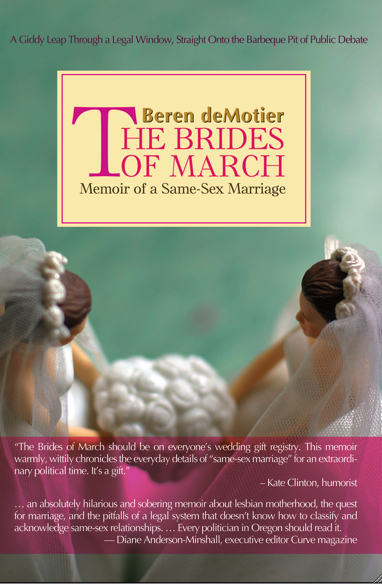

Beren deMotier is the author of THE BRIDES OF MARCH. It’s available on Amazon, of course, but because I always like to plug a good independent bookstore, here’s a link to the book’s page at Powell’s, too.

The Brides of March: Memoir of a Same-Sex Marriage is a lesbian bride’s eye view of marriage at a moment’s notice, with a bevy of brides, their coterie of children, donuts, newspaper reporters, screaming protesters, mothers of the brides who never thought they’d see the day, white wedding cake, and a houseful of happy heterosexuals toasting the marriage. But that was only the beginning as these private declarations of love became public fodder, fueling social commentary, letters to the editor, and the fires of political debate, when all the brides wanted was the opportunity to say “I do” in this candid, poignant, and frequently funny tale of lesbian moms getting to the church on time in Multnomah County.

Anne: One of the aspects of self-publishing — or private publishing, as you like to call it, Mary — that most appeals to aspiring writers is not having to compromise one’s artistic vision (or political vision, or style, etc.) in order to adhere to someone else’s standards. The other, I think, is the comparative speed with which a writer can see one’s work in print. After you committed to your press, how long was it before you actually held your book in your hand?

Mary: I was in the hands of a pro. (Suzie Isaacs at Ampersand.) The process was fast and smooth — I think less than 75 days.

Anne: I remember being stunned at how quickly the book showed up on my doorstep — and how spiffy the production values were. What about you, Beren? From how well put-together the book is, I would have assumed a lengthy turn-around time.

Beren: It was really fast. I think I submitted it on about March 2nd, and it was listed online on April 25th.

Anne: Criminy! Is that a normal turn-around rate for iUniverse?

Beren: I’d asked for an expedited schedule so that I could submit it to the Writer’s Digest Self-Published Book Awards, and iUniverse worked with me to make it happen. Of course, that meant that I had to do my part of the bargain quickly, too; if there were proofs to check, I did them right away.

Mary: There’s no reason, in private publishing, for there to be any delays. Suzie believed in the book and that it should be published, and she kept my spirits up. Every time you write a check—and my total, including 2000 copies, bookmarks, cards, advertisements, posters, etc. was around $20,000 — I needed her affirmations!!

Anne: That sound you just heard was half of my readers’ jaws hitting the floor, I suspect. How close to the actual printing date were you able to make changes?

Mary: On the galleys…I think I had the books two weeks later.

Beren: For me, it was about ten days. I was waiting for a blurb from a famous comedian and hoped it would come before publication. It did, and was able to be fitted on the cover with days to spare.

Anne: Oh, the very idea of that makes me drool. I’m used to dealing with traditional publishing houses, where it’s a year, minimum, between commitment and being able to put one’s hand upon a physical book — after weeks, and often months of discussion between departments on everything from the title (which, for a first book, the writer rarely gets to set) to structure to content. It was especially weird with my memoir, where I kept receiving editorial memos telling me that this or that part wasn’t important enough to include, but that I should add a lengthy section on something that didn’t particularly interest me. It felt as though my life were being edited, not just my book.

What was the editorial process like for you? Were the decisions entirely yours?

Beren: Ultimately, the decision is mine, but they have the right to not brand it as one of their better books should they choose. If I wasn’t able to get positive book reviews, the book wouldn’t be eligible for becoming an Editor’s Choice or Reader’s Choice book, which leads to standard wholesale terms.

Anne: That’s interesting. So if they like it enough, it’s more like going with a traditional publishing house.

Beren: So either it has to be darned good, or you have to pay them big bucks to edit it for you, which takes weeks.

Anne: What about you, Mary? Who got to decide on the book cover, typeface, final edits, et cetera?

Mary: All decisions were mine, but I’m glad that she engaged a top-notch designer who proposed several appropriate options. As to the cover—she did ask what concept I had in mind, and I was a little stuck. My husband came up with dressing up the Lady Justice statue in heels and pearls—the first draft was a bit Betty Boopish, and the graphic designer responded with the modern, sleek image that now is the cover.

I have to say I love the cover, and it does help to sell the book. Yes, people judge the book by its cover, and in this case I really hope they do!

Beren: I’m happy with the outcome, too.I did a lot in creating the look of the book. My spouse took the photo on the cover, and I was able to influence the design, font and colors used in the final product. It became a group project when we shared the photo and necessary copy with friends who all had an opinion on how it should look.

Anne: Did you find having so much control over the final product more empowering or stressful? Or did it depend upon what day it was?

Beren: Hmmm, how about both empowering and stressful?

Certainly knowing that the book would rise or fall based on my work and almost solely my work was a lot of pressure, but I went into it knowing what to expect and had educated myself about the expectations. I feared that the final copy would look photocopied and kind of pathetic, but that didn’t happen.

It seems like it would be nice to hand over a manuscript to a publisher and get a lovely book in return, but I know it isn’t that simple. However, that is my goal—I do want to have a traditional publisher for subsequent books so that there is immediate distribution potential to brick and mortar stores. I consider this my “spec” book, one that I can point to as an accomplished work, as well as eventually sell to a traditional publisher.

Mary: It’s a bit stressful. Even on the galleys, I found a place where I think I had the character approaching the court twice in the same scene.

Anne: But that happens in traditional publishing, too.

Mary: How many people over the years had read these couple of pages, including professional editors, and not noted that? It could drive you crazy. You do need to adopt a certain tolerance for imperfection—we call it being human.

What was the most stressful, however, was the worry that in my acknowledgements I may have failed to mention someone who thought they were important to the work. (I think I did get everyone—at least no one has complained yet.)

For me, the other stress factor is the “autobiographical” accusation: naturally, the book draws on my life experience, but there is no one-to-one correspondence between me and Kathleen Hannigan or any other character and any of my present or former partners or associates.

Anne: And then when you write a memoir, people want to believe that you made things up. It’s as though the fiction and nonfiction labels get mixed up.

Let’s move on to the next stage of the process. Most of us have heard that the biggest hurdles a self-published book has to overcome lie in distribution and promotion. Is that true?

Beren: Yes, I’d say those are the toughest parts. While most self-publishing companies have wholesale channels like Baker & Taylor and Ingram, bookstores are much less likely to buy the book if it isn’t returnable or on standard discounts.

Online, however, the book was readily available fast. It was on Amazon three days after being published, and more online bookstores keep adding it.

Mary: Ampersand set up the Amazon.com, Borders.com and Barnesandnoble.com distribution. I joined the National Association of Women’s Studies Programs in order to have the book listed on their website (and their click-through to Amazon, which benefits the Association if someone buys through that portal.) I also fulfill orders through my website.

Anne: How widely are your books available in bookstores, and how hard was it to set up those venues?

Beren: Locally, I was able to get about six bookstores to carry it, which is a good beginning. The local library bought 13 copies and it has been getting multiple holds.

Anne: Oh, just in case some of my readers are not aware of it, librarians will often order a book if it is requested often enough. I grew up around many, many well-respected authors who would recruit their kith and kin to call their local libraries using different voices to request their books.

I just mention. It also really, really helps authors if enthusiastic readers write reviews and post them on Amazon and B&N. Or in bookstores, to turn the books face-outward, rather than spine-out; a browser is far more likely to pick it up.

Now that traditional presses have shifted so much of the responsibility for promotion onto the author, I’ve been wondering how much more work you’ve had to put into promotion than an author of a similar work at a traditional press.

Mary: I put a fair amount of work into it. I’ve taken charge of sending out free copies to “opinion makers”—something which maybe a traditional publisher would do. I set up speaking engagements, with some help from my publisher.

I have a friend at the Star magazine, and he helped me get listed as the HOT BOOK in one of the October issues. That was a great boost to sales!

Anne: Are you solely responsible for the promotion of your book, or has your press helped you?

Beren: I am solely responsible for the promotion, though occasionally I get offers to pay for co-op advertising through iUniverse, or for them to feature my book at an event. So far, I’ve turned the offers down.

Luckily, my book does have current event appeal, so I’ve been able to get reviews online and in newspapers and magazines. (Gaywired, Mombian, About.com, Just Out), plus a couple of interviews in print and on the radio.

Anne: I’m glad you brought up reviews, Beren, because that’s something that agents and editors always bring up as a serious drawback to self-publishing: most print periodicals in the US, including the vast majority of daily newspapers, have policies that preclude reviewing privately published books. The Internet has really been a boon in terms of getting the word out there.

Your book has also been reviewed, hasn’t it, Mary?

Mary: I was featured in an article in the Chicago Daily Law Bulletin, and will be featured in a special Leading Lawyers publication of women lawyers in Illinois.

Anne: Have you come up with clever ways to promote your book that you

might want to share with us? No matter what press produces your book, ingenious marketing always helps.

Mary: Every time I sell a book, I include 3 postage-paid postcards (of the cover of the book) with a little sell copy on the message side, and ask readers to sign them and send them to 3 friends who might be interested. It’s my version of a viral marketing campaign.

I’d love a couple things: for Hillary or Michelle to carry it around (and I’ve put it in their hands through friends); for women’s studies programs to pick it up for a course on women in the professions—I sent it to Anita Hill and proposed a reading for the National Association of Women’s Studies Programs; for law schools to do the same.

I’ve sent it to some book club leaders, hoping they would recommend it. And a friend is working on the movie option. I sent it to the abovethelaw.com blogger, hoping he’d get interested (he’s a Yalie also). I’ve volunteered to speak at a Brown colloquium at my 35th reunion in May.

Anne: So you’ve been very proactive. What have been your clever promotion schemes, Beren?

Beren: Gosh, well, getting to know cool writers like Anne Mini is always helpful!

Anne: Shameless friends who love one’s writing belong in every writer’s toolkit. I’m constantly being asked by bookstore staff to stop moving my friends’ books to the bestseller tables. But seriously, what else?

Beren: I think contests and awards are a good bet for many writers. I’ve entered about nine for this book, so we’ll see in the spring if it turns out to be a good investment of time and money. With the contests, it involved a lot of copies sent to judges; I just have to trust that they will pay off eventually through wins, word of mouth, getting on the used bookshelves or sheer karma.

I sought out every review I got. I aimed for the specific markets that I knew would be interested in my book, and sent review copies out first thing when I got my 30 free copies. I used every single one for promotion. Eighty percent of those will never be reviewed (and there is a thriving used copy market thanks to me), but enough have that it has helped establish creds for the book, and jumping-off points for other avenues.

I also did a reading and talk at the local library, which was heavily advertised by the county library—there’s nothing like walking in looking for a book on tape and seeing your face in front of you on a poster. I also send out regular e-mails to friends about events and readings.

I did get contacted by an OPB radio interviewer and that was a thrill—she tried to find me!

I could do a lot more, but I’m also balancing freelance work, portrait painting, and raising three kids (two teens and a preschooler with special needs), so I’m kind of busy, though I count my blessings that I’m not also digging ditches eight hours a day on top of it all. I suspect that with a traditional publisher I’d have to do just as much, if not more, but that there would be more tools in place for contacts.

Anne: I’m perpetually in awe of writers who can be productive while caring for small children — possibly because I was for many years a small child being cared for by writers.

Beren: I’ve read several books on finding time to write as a mom, but one of them should address how to stay sane and really write when you’ve got a kid who can’t be out of your sight for a second, really can’t “play quietly” while you type away, and takes every ounce of creative energy to keep growing up uninjured! I’ve yet to read one that recommended a daily dose of Nyquil for the active, irrational tot. Maybe that’s my third book.

Anne: So you don’t have time to have writer’s block? Rats — I was going to ask about your strategies for overcoming it.

Beren: Oh boy, writer’s block — and I just gave up Diet Coke, too, so I can’t recommend guzzling it while at the keyboard. (Have you ever seen a room full of screenwriters at a conference? They all have a can of Diet Coke at their elbow.)

I helped myself get over writer’s block by creating a column with a deadline. It was great training. You have to edit yourself down and cut out your darlings, and you can’t just wait for inspiration to strike.

I do have a fair amount of discipline because I have to to be a writer. Choosing to have three kids and be a writer means jumping in whenever you have the time, or getting a lot done in a short time or taking opportunities as they arrive. These days I sit in my car and write while our youngest is in preschool for 2 hours four days a week, and get up at five for an hour or two before the mob is up.

Admittedly, I’m ready to collapse at eight o’clock at night, but that is how it has to be to get anything done. I’m hoping to have a social life in about five years.

Anne: At the risk of swerving into trite interview territory, what gives you the most inspiration as a writer?

Beren: Well, it is inspiring to know that my grandfather, David Duncan (best known for his screenplay for the 1960 The Time Machine), supported his family of five as a writer.

Anne: That’s a real advantage to being from a family of writers: knowing first-hand that it IS possible to make a living at it. It’s just rare. (And that was a very good screenplay, too, I thought.)

Beren: I also think of author Alice Bloch, who gives herself half an hour a day before working as a technical writer, and got a memoir done that way. I’ve read (Anne Lamott’s) Bird By Bird several times, and love Writing the Memoir, From Truth to Art by Judith Barrington.

Sometimes you care about something so much you have to write about it, and other times (like after walking through a bookstore full of other writers’ work) pride keeps me going: “If they can do it, so can I!” I also keep a file full of nice comments about my writing so that I can look them over if I’m feeling like chucking it in. Every positive thing about my writing that comes my way I grasp onto, to keep me swimming until the next buoy.

Mary: There are, of course, writers I love, but the best resource for me is life itself. I love being active, encountering new experiences, meeting new people, sharing with other writers. I think I actually get the most inspiration from my fellow writers—people like you, Anne, and my friends Julie Weary, Patricia McMillen, Lucia Blinn…the list goes on—all of us next to make it big in the commercial world.

Anne: Oh, I agree 100%: having writer friends in whose work you believe is SO important to keeping yourself going. You can get an incredible boost from a friend’s progress, and you can talk about the hard parts with people who honestly understand. If you don’t share your hopes and fears, they can so easily turn into the demons of self-doubt.

Which leads me to ask a totally unfair question that I think will be wildly interesting other writers: what was your biggest fear in embarking upon self-publishing, and did it actually come to pass?

Beren: That bookstores would laugh in my face if I came in with my book to sell on consignment. It only happened once (she didn’t actually laugh, but the condescending note was very present), though after talking about it with her, she admitted it might be a book they wanted to carry and took one new copy. Since then, they’ve sold several used copies, and carry it online.

Anne: I love it when the fears turn into triumphs. What about you, Mary?

Mary: My biggest fear is that I would end up with a living room full of boxes of books—that my friends would each buy one and that would be it.

I never expected that at a reading someone I’ve never met would march up to the table and buy 10 copies for her friends—and be sending them to friends in India and Pakistan and England! I do have a few boxes in my living room, but sales have been brisk.

Anne: So your demon of fear mutated into a triumph, too. That’s great.

Mary: I was also afraid that people would assume that because it was self-published, it wasn’t any good. But people don’t “get” that it is self-published. They just know it IS published.

Anne: That fascinates me, because we’re so often heard the opposite asserted at writers’ conferences. But then, I suppose agents and editors at traditional publishing houses don’t often have much contact with self-published authors — or at any rate, didn’t until fairly recently. I’ve keep meeting authors who published their own first books and were picked up on their next because the first sold so well.

Okay, I’ve been holding off on this next question, because I try not to deal in superlatives; life’s all about the gray areas, after all. But here it goes anyway: so far, what has been the best thing about the self-publishing

process for you?

Mary: It’s been fun! I’ve heard from people I’ve lost touch with—like I hadn’t spoken to them in 12 or 13 years, and they’d write and call and thank me for writing the book and say that they could totally relate to it.

Beren: The best thing was that it was fast, and I learned a lot about book creation and publishing. The more I know about the artistic and business aspects of writing, the better I will be (I trust), and no effort was wasted.

Anne: What has been the worst part?

Mary: The worst — sorry, N/A.

Anne: I’m really pleased to hear that.

Mary: My own worry, my own bruised ego.

Anne: Which are endemic to the querying and submission process, too. What do you think, Beren?

Beren: The worst part is that there are limitations to a self-published book in terms of wider wholesale distribution unless you self-publish yourself as a small press, or sell a certain amount of copies already (as in the case of iUniverse). Getting books in bookstores on a big scale is challenging.

Anne: I already asked Mary this last time, but if you had only a minute to give advice to someone who was thinking of self-publishing, what would you say?

Beren: Do your research, know your goals for publication and work very very hard at making your manuscript the best it can possibly be. On one writing weekend, after the book was essentially finished, I worked at making it the very best it could be, sentence by sentence, word by word, and in two long days I got forty pages done. But they were much better pages.

Work with the editor at the press or hire an editor, take your work seriously. It is important work.

Mary: Yes, invest in a manuscript editor so that you will have the confidence that your work is ready and deserving of being in print.

Anne: To sound like an agent for a moment, congratulations on your current success — what’s your next project?

Beren: I am currently gathering a collection of humorous stories about life in the lesbian mom trenches, reworking some old favorites and putting them together as a book I’m calling Maggots Before Breakfast, and other Interesting Adventures in a Cozy Liberal Enclave.

Anne: Literal maggots or figurative ones?

Beren: There is a story about maggots, and the original piece is on my website. I plan on pitching it to traditional publishers, using the kudos The Brides of March has garnered, as well as the platform I’m building through appearances, blogging, and articles.

Mary: I have a shopping bag full of novels. My most recent was a short-list finalist for the William Wisdom/William Faulkner Prize, and I am actively looking for an agent for that one. I do think it would be harder to self-publish a novel that is “just a literary novel” which is less directed to a particular audience. I would self-publish again, if it comes to that.

My most immediate “next writing project” is the made-for-television version of my musical Fairways, which will require some rewriting for the pilot (to be filmed in April/May), and finishing the script for my next musical, “We’re Cruising Now, Babe!”

Anne: Well, please come back and tell us all about these projects down the line.

I can’t thank you enough for sharing your insights with us — I’ve truly enjoyed hearing aobut your experiences. Best of luck with your books, and as we like to say here at Author! Author!, keep up the good work!

Beren deMotier has written humor/social commentary for Curve, And Baby, Pride Parenting, Greenlight.com, www.ehow.com, as well as for GLBT newspapers across the nation. She’s written about same-sex marriage for over a decade, and couldn’t resist writing the bride’s eye view after marrying in Multnomah County. She lives in Portland, Oregon, with her spouse of twenty-one years, their three children, and a Labrador the size of a small horse.

Ever since turning 40 a few years ago, Mary Hutchings Reed Mary has been trying to become harder to introduce, and, at 56, she finds she’s been succeeding. Her conventional resume includes both a bachelor’s and master’s degree from Brown University (both completed within the same four years, and she still graduated Phi Beta Kappa), a law degree from Yale, and thirty-one years of practicing law, first with Sidley & Austin and then with Winston & Strawn, two of the largest firms in Chicago. She was a partner at both in the advertising, trademark, copyright, entertainment and sports law areas, and now is Of counsel to Winston, which gives her time to write, do community service and pursue hobbies such as golf, sailing, tennis, and bridge.

For many years, she has served on the boards of various nonprofit organizations, including American Civil Liberties

Union of Illinois, YWCA of Metropolitan Chicago, Off the Street Club and the Chicago Bar Foundation. She currently serves on the board of the Legal Assistance Foundation of Metropolitan Chicago (and chair of its fundraising committee); Steel Beam Theatre, and her longest-standing service involvement, Lawyers for the Creative Arts.