Hey, do you know what today is? It’s the one-week anniversary of the announcement of my blog’s entrée into the serious award-granting stage of its career, First Periodic Author! Author! Awards for Expressive Excellence. Not only is that a prize win that would look awfully pretty on a query letter or in an author bio — hey, I worry about the progress of your writing career, you know — but it’s a chance for those of you who feel strongly about the subject of our ongoing series on censorship, subtle and otherwise, to get your work published side-by-side with some pretty impressive published authors.

Oh, and there are some more tangible prizes as well. You’ll find the rules here. Chief among them: in order to win or place, an entry must be in standard manuscript format.

Why, what a remarkable coincidence: we seem to be in the midst of a series on standard format! The universe sure works in mysterious ways, doesn’t it?

Which means, of course, that it’s time to get back to work. Has everyone recovered from the last few days’ worth of inoculation with professional formatting know-how?

Yes, that was a whole lot of information to absorb at once, and it may have left a bit of a sore place, but much better a one-time quick sting than engendering years of rejection without knowing why, I always say. Once you’ve gotten exposed to the correct way to format a book manuscript, chances are that you’ll be immune to formatting problems in the future.

Why, yes, I have run that metaphor right into the ground. How kind of you to notice.

There’s a reason I’m hammering on it so hard, however: one of the great fringe benefits of inoculation is that, as unpleasant as it may have been at the sticking-point, so to speak, the stuck usually doesn’t have to think all that much about smallpox or whooping cough for quite a long time afterward.

So too with standard format for book manuscripts — once a writer gets used to how a professional submission is supposed to look, everything else is going to look wacky.

No, really. As I have been threatening begging you to believe against all evidence promising you repeatedly every few minutes while running through the standard format strictures, once you get used to how a professional manuscript is put together, any other formatting is going to feel downright uncomfortable.

And to prove it to you, I’m going to spend the rest of this series let you see precisely HOW different standard format and non-standard format appears to the pros.

But first, the usual caveats: what I’m about to show you is for BOOKS and BOOK PROPOSALS only, folks. At the risk of repeating myself (and repeating myself and repeating myself), I’ve been talking for the last few days ONLY about how books and book proposals should be formatted, not about short stories, screenplays, poetry, magazine and newspaper articles, or anything else; if you’re looking for formatting tips for any of the latter, run, don’t walk, to consult with those knowledgeable souls who deal with that kind of writing on a day-to-day basis.

Translation: first, if the agent or editor of your dreams (or the agent or editor with whom you are currently signed, if they don’t happen to be the same person) has expressed a strong preference for his clients formatting in a manner opposed to what you see here, run with that — but only for submission to that particular agent.

Yes, major deviations from this format are genuinely uncommon — among manuscripts that agents are currently submitting to editors at major US publishing houses, at least — but let’s face it, you’re not going to get anywhere telling an established agent that no one else’s clients are using 18-point Copperplate Gothic Bold if he happens to have an unnatural affection for it. Part of working with an agent entails trusting that he knows more about marketing books than you do. If he doesn’t, you wouldn’t WANT to be working with him, right?

I must have misheard all of the query-weary submitters out there. The proper answer is YES.

And before my last statement sends anyone out there into that time-honored writerly I’ve just signed with an agency but what if I chose the wrong one? panic, remember this: if you’ve done your homework before you signed, and thus are certain that he has a solid recent track record selling books in your category, you have every reason to have faith in your representative.

Or so I keep telling myself when I can’t sleep at night. Handing one’s hopes and dreams to someone else to market is hard.

Second, please recognize that not everything that falls under the general rubric writing should be formatted identically. So if your favorite source — other than yours truly, of course — tells you to do something diametrically opposed to what I’m showing you here, may I suggest double-checking that the other source is indeed talking about book manuscripts and not, say, submissions to a magazine that accepts short stories?

I hate to burst anyone’s bubble, but contrary to popular belief, submission standards differ by type of publication.

Yet surprisingly often, those giving practical to aspiring writers will conflate the format for, say, short stories, one with that for book manuscripts, resulting in a first page that will look incorrect to either. (Although, generally speaking, such guidelines tend to stick closer to the short story format than to the book.)

Don’t worry; I’ll be showing you the first pages of both very soon. In the spirit of that old chestnut, SHOW, DON’T TELL, I shall demonstrate just how different a manuscript that follows the rules looks from one that doesn’t.

But not before I give you just one more reason to study these examples very, very carefully if you are planning to submit book-length work to a North American agent or editor anytime soon: writers often overlook odd formatting as a possible reason that an otherwise well-written manuscript might have been rejected.

Oh, not all by itself, generally speaking, unless the violation was truly egregious by industry standards, something along the lines of submitting unnumbered pages or not indenting paragraphs, for instance. But in a garden-variety well-written manuscript that combines non-standard format with even just a couple of the common agents’ pet peeves — a cliché on page 1, for instance, or several misspellings in the first paragraph — the result is generally fatal.

Certainly, other rejection reasons get a lot more airplay, particularly at writers’ conferences. If you want to take a long, hard look at some of the better-discussed reasons, I would urge you to gird your loins and plunge into the REJECTION ON PAGE ONE category at right. (For those of you who missed it this past January, I went over list of instant-response rejection reasons given by a group of agents going over a stack of actual submissions at a conference, one by painful one. Pretty horrifying.)

Yet surprisingly little conference time seems to be devoted to deviations from standard format for manuscripts. Why shouldn’t conference speakers take thirty seconds of their speaking gigs to pointing out, for instance, that the ways in which a professional manuscript does not resemble a published book — ways that are unfortunately quite obvious to an agent, editor, contest judge, etc., from practically the moment their eyes light upon a submission?

Why is it so very apparent, you ask? Because much of the time, submitting writers will work overtime to make it apparent.

Seriously, many aspiring writers clearly go out of their way to format their submissions to resemble published books, in the mistaken belief that this will make their work seem more professional. As we’ve already discussed in this series, the opposite is generally true — and often, it’s apparent in a professional reader’s first glance at the first page of a submission.

If the implications of that last assertion made you dizzy — if, for instance, you found yourself picturing our old pal Millicent the agency screener pulling a submitted manuscript out of its envelope, casting a critical eye over the first page, hooting, and stuffing the whole thing into the handy SASE along with a photocopied rejection letter — try placing your head between your knees and breathing slowly.

Go ahead. I’ll wait until you recover.

And then follow up with a hard truth that may get those of you new to the game hyperventilating again: the VAST majority of submissions are rejected not only on page 1, but within the first few lines of page 1. Heck, a harried Millicent will derive a negative impression of a manuscript even PRIOR to page 1.

Keep taking nice, deep breaths. That dizziness will pass shortly.

Ah, some of you have found your breaths again, haven’t you? “Oh, come on, Anne,” I hear some hard-boiled submission veterans scoff, “she makes up her mind prior to page 1? How is that even possible?”

Well, the most common trigger is the absence of any title page whatsoever. Many submitters, for reasons best known to themselves, omit the title page altogether — often, I suspect, because they are unaware that a professional book-length manuscript ALWAYS has a title page.

Why? Long-time readers (or even those who have been paying attention over the last several days), chant it with me now: a properly-formatted title page tells an agent PRECISELY how to contact the brilliant author who wrote it — and tells an editor PRECISELY how to contact the agent who represents her.

To set the minds of those of you who have title page-free submissions circulating at the moment, relax: forgetting to include a title page almost certainly won’t prevent Millicent from reading your submission at all; she tends to read even the most bizarrely-formatted submissions for at least a line or two (although often no more than that). But that initial impression of an author’s lack of professionalism — or, to call it by a kinder name, of having a lot to learn about how the publishing industry works — does often translate into a rather jaundiced reading eye for what comes next.

Why? Well, let’s take a peek through her reading glasses, shall we? The first thing Millicent sees when she opens the average requested materials package is something like this:

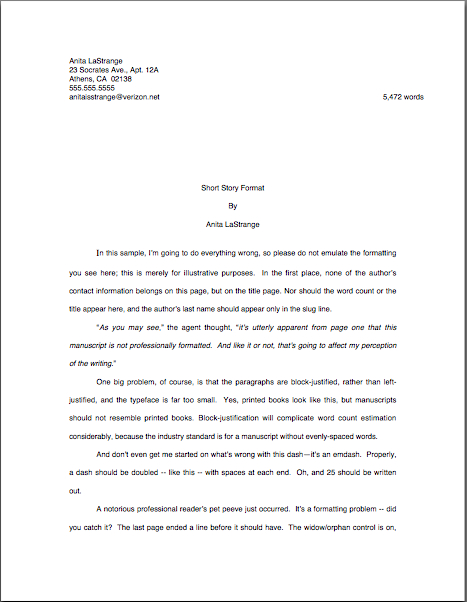

Or like this:

Or, heaven help us, like this:

So tell me: why might Millicent take one look at these and conclude that their respective submitters could use a good class on manuscript formatting — and thus would be time-consuming clients for her boss to sign?

I see all of you long-term blog readers out there with your hands in the air, jumping up and down, eager to tell everyone what’s wrong with this as a first page of text — and you’re absolutely right, of course. We’re going to be talking about precisely those points in the days to come.

For now, however, I want you to concentrate upon how this example has failed as both a title page and a first page of text: by not including the information that Millicent would expect to see on either.

What makes me so sure she would find this discovery disappointing, at best? Because what she (or her boss agent, or an editor, or a contest judge) would have expected to see on top of that pile of paper was this:

This is a standard manuscript title page for the same book — rather different, isn’t it? Visibly different, in fact, from several paces away, even if Millicent isn’t wearing her reading glasses.

Again, submitting the earlier examples rather than that last would not necessarily be instantly and automatically fatal to a manuscript’s chances, of course. Most of the time, Millicent will go ahead and plunge into that first paragraph of text anyway.

However, human nature and her blistering reading schedule being what they are (for those of you new to this screener’s always-rushed ways, she has a stack of manuscripts up to her chin to screen — and that’s at the end of a long day of screening queries; manuscript submission is in addition to that), if she has already decided that a submission is flawed, just how charitable an eye do you think she is likely to cast upon the NEXT problem on the page?

To use her favorite word: next!

To be fair to Millicent, while it may well be uncharitable of her to leap to the conclusion that Faux Pas’ or Ridiculous’ manuscript is likely to be unpolished because they did not include a proper title page, agencies do have a vested interest in signing writers who present themselves professionally. For one thing, they’re cheaper to represent, in practical terms: the agent doesn’t have to spend as much time working with them, getting their manuscripts ready to submit to editors.

And no agent in his right mind would send out a manuscript that didn’t include a standard title page. It serves a number of important — nay, vital — marketing functions.

To understand why, let’s take another look at the professional version. So you don’t have to keep scrolling up and down the page, here it is again:

Did you take a nice, long look? Good. While we’re at it, let’s also take a gander at a proper title page for a book with a subtitle (I haven’t forgotten your question, Harvey!):

Those formats firmly in your mind? Excellent. Now for a pop quiz: how precisely do Rightly and Collie’s first sheets of paper promote their respective books than Faux Pas or Ridiculous’ first pages?

Well, right off the bat, the good examples tell a prospective agent or editor what kind of book it is, as well as its approximate length. (If you do not know how to estimate the number of words in a manuscript, or why you should use an estimate rather than relying upon your word processor’s count, please see the WORD COUNT category at right.) Both of these are pieces of information that will tell Millicent instantly whether the submission in her hand would meet the requirements of the editors to whom her agency tends to sell.

Oh, yes, that’s important in a submission, whether to an agency or a publishing house. Really, really important.

Why? Well, think about it: if Millicent’s boss had decided not to represent Action/Adventure anymore, or if editors at the major houses had started saying that they were only interested in seeing Action/Adventure books longer than 90,000 words, Rightly Stepped would be out of luck.

But then, being a savvy submitter, ol’ Rightly would also want his work to be represented by an agent who just ADORES very long Action/Adventure novels — and regularly goes to lunch with scads and scads of editors who feel precisely the same way, right?

As I MAY have mentioned seven or eight hundred times before (in this post, it feels like), the standard title page also tells Millicent precisely how to contact the author to offer representation — and that’s a very, very good thing for everyone concerned. If I’ve said it once, I’ve said it a thousand times: it’s ALWAYS in an aspiring writer’s interest to make it easy for an agent to help her.

I might be wrong, of course, but I suspect that NOT forcing Millicent to forage through the mountain of paper on her desk to find a misplaced cover letter with your phone number on it MIGHT be a good start toward being easily helpable.

By contrast, Faux Pas’ first page doesn’t really do anything but announce the title of the book and leap right into the story. That’s one underachieving piece of paper.

Some writers attempt to consolidate the proper functions of the title page and first page of text into a single sheet of paper. This format is particularly common for contest entries, for some reason. Let’s take another look at Ridiculous and Faux Pas’ submissions:

While such a top page does indeed include the requisite information Millicent or her boss would need to contact the author (although Faux Pas’ does it better, by including more means of contact), cramming it onto the first page of text doesn’t really achieve anything but saving a piece of paper. It doesn’t even shorten the manuscript or contest entry, technically speaking: the title page is never included in a page count; that’s why pagination begins on the first page of text.

I shall go into what DOES belong on the first page of text tomorrow, with accompanying visual aids. For today, let’s keep our focus simple: all I ask is that you would look at the proper title and the unprofessional examples side by side.

Go back and look again. I’ve got some time to kill.

Got all of those images indelibly burned into your cranium? Good. Now weigh the probability that someone who reads as many manuscripts per day as Millicent — or her boss, or the editor to whom her boss likes to sell books — would NOT notice a fairly substantial difference in the presentation. Assess the probability of that perception’s coloring any subsequent reading of the manuscript in question.

The answer’s kind of obvious once you know the difference, isn’t it?

Before I sign off for today — and while you’ve got R.Q. Snafu’s example still in the front of your mind — let me briefly address the still surprisingly common writerly belief that the agents and editors will automatically take a submission by a woman more seriously if the author submits it under her initials, rather than under her given first name.

J.K. Rowling aside, this just isn’t true, at least in fiction circles.

So unless you have always hated your parents for christening you Susan, you won’t really gain anything professionally by using initials in your nom de plume instead. And even if you did, why not publish under a name you actually like instead?

That’ll show your Susan-loving parents.

I just ruffled a few feathers out there, didn’t I? “But Anne,” I hear an initialed purist exclaim, “I don’t want to be judged as a FEMALE writer — I want to be judged as a WRITER. What’s wrong with removing gender markers altogether?”

Well, there’s nothing wrong with it per se, Susan, except that these days, it almost invariably results in Millicent’s seeing such initials and thinking, “Oh, this is a female writer who doesn’t want to be identified as one,” rather than “Gee, I wonder who this mystery person without a first name is. I’m just going to leap right into this manuscript with no gender-based expectations at all.”

Why will Millie have this reaction, you ask? Because female writers — and with a few notable exceptions, almost exclusively female writers — have been submitting this way for a couple of hundred years now. It’s not all that hard a code to crack.

Historically, the hide-my-sex-for-success strategy has been used far, far less by male authors — except, of course, that hugely prolific and apparently immortal author, Anonymous, and the reputedly male writers of such ostensibly female-penned classics of wantonness (avert your eyes, children) as THE HAPPY HOOKER and COFFEE, TEA, OR ME?. Even during periods when the most popular and respected novelists have been women (and there have been quite a few in the history of English prose, contrary to what your high school English textbook probably implied), when someone named Stanley Smith wrote a novel, the title page has generally said so.

Because, you see, even back then, readers would have assumed S. Smith the novelist was a nice lady named Susan. It’s probably where your parents got the idea to christen you that.

Something else for initial-favoring fiction writers to consider: in North America, women buy the overwhelming majority of novels — and not just women’s fiction, either. Literary fiction readers (and agents, and editors) tend to have two X chromosomes — and some of them have been known to prefer reading books by Susans rather than Roberts.

I just mention.

All that being said, the choice to initial or not is entirely up to you — or, more accurately, to you and your agent. Some sets of initials look cool in print, just as some names look better than others on book jackets.

Or so claimed my father, the intrepid fellow who demanded that the maternity ward nurse convey him to a typewriter to see how my name looked in print before committing to filling out my birth certificate. You know, to see how if it would look good on a book jacket. So for those of you who have wondered: Anne Mini IS in fact my given name; it just happens to look great in print, thanks to a little forethought.

Keep your chin up, Susan — you have some say in what the literary critics will call you. And keep up the good work!